Caster Semenya is a reminder that we need more human rights in sport

Posted by Macduy Ngo

From locker rooms to board rooms and from TV screens to stadiums, the language of human rights is increasingly embedding itself into the sporting landscape.

The focus of this scrutiny has been on large-scale sporting events and their impact on workers and communities: the plight of migrant workers building infrastructure for the World Cup 2026 in Qatar, alleged ‘social cleansing’ of favelas ahead of the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, and supply chain labour standards in relation to the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic games. While undoubtedly important, these headline cases should not overshadow issues at smaller sporting events, or gloss over the human rights challenges faced by other rightsholders such as athletes and fans. These groups are equally crucial to the functioning and enjoyment of sport.

As the world of human rights and sport develops, there also needs to be a greater appreciation for what makes the sporting context different when considering human rights impacts. The considerable power imbalance between coach and athlete and the proximity of this relationship, particularly at lower or youth levels of competition, is perhaps one idiosyncrasy – one need only look at the USA gymnastics sexual abuse scandal. The fact that sports remains a bastion of gender segregation, requiring ‘bright line’ rules seeking to allocate gender, is another. Therein lies the challenge of the Caster Semenya decision by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) – a much anticipated ruling that underscores some of the unique human rights challenges that arise in the sporting world.

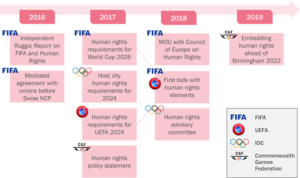

Selected human rights milestones in the world of sport

Caster Semenya

Semenya, an accomplished middle-distance runner, challenged a rule by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) that seeks to determine the eligibility of athletes to compete as male or female. The IAAF’s Differences of Sex Development (DSD) regulations rely on testosterone measurements: female athletes with XY chromosomes who have a testosterone level over 5 nmol/L (the typical female level is below 2 nmol/L) and who experience a ‘material androgenizing effect’ from these enhanced levels must reduce their testosterone level to below the threshold in order to compete as a female athlete in certain events. Such reduction can be achieved through oral contraceptives, according to the IAAF. Such therapy is reportedly associated with various side effects, including increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Semenya, whose testosterone levels are such that she has had to undergo hormone therapy (adding 4% to her 800 metre time), challenged the DSD regulations on the basis that they were discriminatory, unnecessary, unreliable, and disproportionate. In its decision the CAS ultimately upheld the IAAF’s DSD regulations, although the full text has not yet been released. While the DSD rules were found discriminatory, such discrimination was viewed as being necessary, reasonable, and proportionate to the aim of preserving ‘integrity’ in female athletics. The implication of this decision for non-binary athletes is obvious.

Athletes as an oft-neglected rightsholder

The Semenya decision serves as a reminder that athletes are often neglected as rightsholders. There have been other recent cases, to be sure: Colin Kaepernick’s act of protest, and FIFA’s (now lifted) ban on head covers impacting hijab wearing footballers both provide useful examples. ‘Blue chip’ athletes who are monied and influential do not easily align with our understanding of ‘vulnerability’ – a driver of much human rights analysis. This perspective plainly neglects the legitimate concerns raised by such athletes and also omits scores of amateur athletes who do demonstrate a range of vulnerabilities. The #Metoo movement’s spillage into sports, innumerable hazing incidents, and racial taunting of amateur players offer a sobering counterfactual.

For similar reasons, athletes are also typically not viewed as ‘workers’, an otherwise familiar rightsholder in human rights analyses though the unionisation drive of college athletes in the U.S. – predicated on their status as workers – challenges this.

What’s next for Semenya?

It is unlikely that the CAS decision will be the final word on the IAAF’s testing rules; an appeal to the Swiss Federal Tribunal is available. The court of public opinion is also having its say.

Moreover, the CAS decision hardly represents an ironclad endorsement of the DSD regulations. The CAS Panel was careful to note that while the rules are proportional on their face (thus helping to ‘justify’ the discrimination), there are a number of questions as to their practical implementation. Potential issues include the side effects of hormone treatment, the reliability of evidence that there is a testosterone-related advantage in certain events, and the consequences of unintentional non-compliance.

It is significant that the CAS Panel found it necessary to voice its concerns on questions that, strictly speaking, go beyond the question that was submitted to arbitration. This should send a strong signal to the IAAF (and other sports governance bodies) that the application of its rules and any subsequent revisions will face careful scrutiny.

The CAS Panel’s discomfort, as well as the diversity of commentary that has been spawned by the decision, is a reminder that an easy solution is not forthcoming. Advocates of a ‘third’ category for athletes who are neither male nor female in the eyes of sports governance bodies simply shift the goal posts – arbitrary rules must still be used to define who falls into this third category. More importantly, such a proposal should surely raise questions of athlete dignity and the possibility for further stigmatisation.

The best we can hope for is an approach that is developed in consultation with non-binary athletes and compatible with human rights principles to the fullest extent possible.

For questions relating to Ergon’s sports and human rights practice, contact Steve Gibbons at [email protected] or [email protected]