Platform work in emerging and developing countries: potential and pitfalls

Posted by Genevieve Auld

Ergon has advised our development finance clients on the decent work aspects of a number of platform work transactions, and this blog explores some of the issues we have analysed and the potential safeguards that digital platforms and investors may need to consider to maintain labour standards.

As we explored in a previous blog, the gig economy continues to generate both positive and negative headlines: as an opportunity for more flexible work and create job pathways for traditionally informal markets, but also a potential source of worker precariousness. In response, countries are grappling with how to regulate the gig economy in line with worker and market needs. For example the UK Supreme Court decision has found Uber drivers are workers (with the legal protections that brings), while India has announced plans to extend some social protections to platform workers.

Yet, while the majority of commentary has focused on regulation in advanced economies, the gig economy is a large source of employment in emerging and developing countries – it is estimated that 40 million people in emerging and developing countries are registered in the platform economy. It also offers opportunities for economic growth and a pathway to formal employment. And it is rapidly expanding. For example, in Kenya, more than 60% of gig workers joined between 2017-2021.

Platform work refers to a digital infrastructure (such as a phone app) that brings together workers and customers. The digital labour platform matches customers requesting services with workers. Workers providing services through platform work are often described as ‘gig workers’ or working in the ‘gig economy’ referring to the often temporary or project-based nature of the work. Examples of platform work include ridesharing or taxi services, deliveries and cloud or online based work.

The gig economy as a development pathway?

There has been an increasing recognition that digital labour platforms represent development opportunities in developing and emerging regions – where 93% of informal employment is concentrated – such as in Sub-Saharan-Africa, and in India.

Platform work can contribute to formalisation – while not representing fully formal employment – bringing benefits to workers such as payment via a bank account and certainty of payment. There is also some evidence that it creates employment opportunities for vulnerable groups who may otherwise struggle to find work, such as women, young people, refugees and migrants (although some groups such as refugees and forcibly displaced persons remain excluded because of lack of identity documents).

Developing and emerging countries also benefit from the job creation that has the potential to transform economies – it is estimated that platform work could create 90 million jobs in India. It is also argued that the platform economy is responsive to market needs and may help provide services that are otherwise limited. For example, in Kenya, there is now a platform based ambulance service that connects private ambulances with patients in emergency situations.

Challenges with the platform economy in developing countries

Despite the shift towards the formality through platform work, there remain significant risks to workers engaged in the platform economy as they may not benefit from adequate worker protections and legal safeguards.

The majority of gig workers in developing and emerging countries are likely to remain outside the protection of labour laws if classified as ‘independent contractors.’ This employment status may also limit access to other legal protections such as health and safety, and social insurance or social security protection. According to the ILO, the majority of workers in the platform economy have no social security coverage. This is particularly problematic in countries which may not have strong public health or social insurance protection systems.

Additionally, in some developing and emerging countries, there may be insufficient competition or antitrust regulation or enforcement to prevent certain digital labour platforms having excessive market concentration to the detriment of both workers’ ability to negotiate, and also for the wider economy.

‘Institutional voids’ and decent work

As legal regulation, oversight or enforcement struggles to keep up with the pace of development of the gig economy, digital labour platforms have been described as operating in ‘institutional voids’, meaning that platforms have the ability to set the terms and conditions for workers and customers resulting in insufficient protections of their rights, and limited accountability or access to remedy for worker grievances. Workers in particular are at risk of digital labour platforms shifting responsibility for legal compliance (such as health and safety) and costs (such as required tools and equipment) while setting insufficient rates of payment resulting in worker precarity. This places responsibility on the platforms, and their investors, to create and ensure adequate safeguards.

Understanding platform features that create decent or precarious work

As a starting point, digital labour platforms and investors need to consider the features of the platform and whether it creates opportunities for decent work. These opportunities arise from both the platform characteristics and the type of work being undertaken. Given the variance in digital labour platforms, local conditions, and worker characteristics, the risks and vulnerability may play out differently.

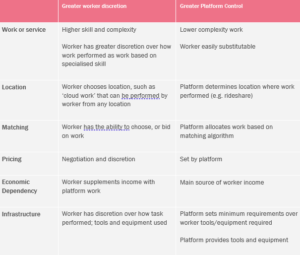

The below table outlines some common features of platform work that may impact on the quality of jobs created by platform work.

Additionally, platforms and investors can consider the following dimensions of decent work to evaluate whether platform work provides the necessary safeguards against vulnerability:

While the platform economy represents opportunities for economic development, it also needs to lead to create the conditions for the development of decent work. Digital labour platforms and development finance investors share a responsibility for ensuring that this is the case.