Corporate Human Rights Benchmark reports slow progress

Posted by Matthew Waller

The Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB) has launched its second analysis of the human rights practices of 101 of the largest global companies across the extractives, apparel and agricultural products sectors. The Benchmark compares companies’ human rights practices across six ‘measurement themes’ in a bid to highlight which companies are performing best (and worst) in relation to key human rights issues as an incentive to drive change across these sectors. Companies receive a score on each theme and a total score based on public disclosures and additional information supplied to CHRB which is also then made public.

Key findings

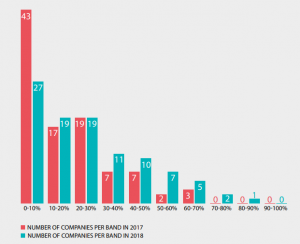

Whilst this year’s average total scores went up by 9 percentage points compared to the 2017 pilot benchmark, this increase only took the total average to 27% (from 18%), which, according to the CHRB, is still ‘alarmingly low’. More than a quarter of companies had a total score of less than 10%.

Some of the other key concerning findings highlighted by CHRB were:

- ‘the stark gap between the leading companies and those in the lower scoring bands’, a disparity that CHRB feels could become more entrenched;

- that 40% of companies do not demonstrate that they have a human rights due diligence process in place, which is fundamental to identifying and addressing human rights issues;

- land rights was one of the worst scoring indicators of the Benchmark, with 80% of extractive companies and all of the 11 relevant agricultural companies scoring zero points for their own operations;

- the majority of companies with supply chain risks do not align their purchasing practices with human rights principles, despite this being a key driver of worker vulnerabilities in global supply chains; and

- only 7% of companies have made public commitments stating that they will not tolerate abuse of human rights defenders, highly worrying at a time when there is an increasing number of violent attacks on individuals who are standing up to and trying to expose corporate and government abuses.

The CHRB states that, ‘seven years after the UNGPs were agreed and launched, the 2018 Benchmark finds many companies in high-risk sectors are not demonstrating a respect for human rights’. This statement may be hard to deny, but it may also be that CHRB is being unduly pessimistic in its assessment. There are too many companies still in the bottom decile, but that number has fallen by more than a third. Equally, there are now 36 companies scoring more than 30%, as opposed to only 19 companies in the first iteration. It might be slow, but there is progress in terms of average scores and over a relatively short period. The question is: how fast should we reasonably expect progress to occur? And can exercises based on public disclosures capture and measure performance and progress?

Some challenges in the approach

As CHRB is aware, their findings are only as good as the data companies put in the public domain. Obviously, companies may choose not to disclose what they are doing with regards to human rights. This practice is common, and we see that many of our clients actually do considerably more on human rights than they are comfortable talking about. Conversely, it is also the case that publicly disclosed information can overclaim what actually happens in practice. Without stricter, more defined standards on mandatory disclosure and due diligence there is unlikely to be a level playing field on reporting as companies are not obliged to do or talk about human rights practices.

Additionally, the CHRB process does not really address the question of whether companies’ practices are actually having an impact across their operations and supply chains. A total of 48 companies faced serious human rights allegations, which, interestingly, included all those top performing companies in the Benchmark (companies score well if their response is deemed to be appropriate). We have no idea if a lack of allegations means a company’s due diligence processes are working, and whether this is better than responding well to an actual serious human rights impact. Many abuses are not widely reported and can take place in countries where civil society activities and press freedoms are limited. These contextual factors are obstacles we regularly have to consider and overcome when thinking about human rights risks for clients.

Ultimately, the results of a benchmark such as the CHRB should be taken as an indication of a company’s intent and approach to managing human rights risks. Is this useful? For companies, it certainly could be. Inspiration should be drawn from the likes of Adidas, Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton and M&S, who all demonstrate that it is possible to score well, and from another group of companies such as ENI, Vale, Diageo and Danone that have made rapid and significant progress since the first Benchmark results. Higher scores also show that transparency is not damaging to businesses.

The CHRB was partly set up by institutional investors (notably Aviva) and its results are intended to inform investment decisions. The jury is out on whether it can achieve this aim. While scores give an idea of the relative performance of companies, and indicate areas of strength and weakness, it is probably too detailed for portfolio investors with hundreds of companies in their funds, many of which will be outside the ambit of the Benchmark. Rather than being used by investors (other than the three institutions backing it), it is more likely that Benchmark scores will be used primarily by companies themselves to assess where they stand relative to their peers. If it creates a race to the top, then its aim will have been achieved.

What next?

In the short term, the CHRB is expanding coverage to ICT companies in its next iteration. But it faces the tricky task of meeting its desired goal in pushing companies to improve their human rights practices without deterring them from engagement in the process. For example, though companies are given the opportunity to respond to the findings with new evidence that may change their scores, not all do, and when they do it is rare that it changes anything. In many respects, the fact that companies cannot easily sway a decision demonstrates the robustness of the CHRB methodology, though it could also be a factor in deterring company engagement in the process, a principle upon which the Benchmark is premised. Balancing how best to negotiate this dilemma will be important for the continuing relevance of the benchmark.

That there seems to be increasing engagement on this issue is a positive trend, but it will be important that the CHRB keeps up this momentum in coming years to make the desired impact. As discussed at the launch, the methodology will need to maintain a degree of consistency to allow for year on year comparison, yet it will also require a degree of flexibility to meet future challenges and priorities – note this year’s discussions of climate change as the key human rights challenge of the future.

In all this there is a wider question about the role of benchmarks like CHRB, especially when the field is becoming crowded. The CHRB and others are coming together through the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) to see how they can use their partnership to maximise their transformative impact on business. But will benchmarks have this effect? There is a danger that beyond the handful of leading companies, many will be content with ‘mid-table mediocrity’. As we have found in respect of Modern Slavery Statements, naming and shaming, combined with some investor and NGO pressure, may only go so far. Governments will probably need to level the playing field by requiring more of companies operating in their jurisdictions. Until then, there is a responsibility on leading companies to continue to set an example, for civil society to give them credit where credit is due, and for investors to engage more actively on these issues.